Dr. Doris A. Derby is an activist, photographer, educator, and scholar, who spent ten years in the civil rights movement in Mississippi. Her life and career are reflections of her commitment to the arts as a means of uplift for African Americans. Engaging a grassroots, bottom-up approach, Derby has used cultural heritage to address the problems and issues of every community she has served, a strategy and philosophy that became the calling card of activists and the modern movement. This essay highlights Derby’s work within the movement as well as her documentation of Black cultural life and organizing traditions.

"Creative expression is the pulse that keeps us alive. The creativity keeps coming, connecting, reflecting years of history in the making.”

For Derby, folklife was a natural expression of Black resilience, and it could appear in a plethora of artistic ways. “The creativity of the arts reflects daily interests, influences, experiences and occurrences of real people’s lives, which help to continue the traditions as well as promote beliefs and expressions between Blacks in the North, South, East and West, town, city and country. Intergenerational creative networks keep growing like well-rooted cultural vines, striving higher and higher and proliferating into many new strains. Creative expression is the pulse that keeps us alive. The creativity keeps coming, connecting, reflecting years of history in the making.” 1

Born in New York City on November 11, 1939, Derby earned her Bachelor of Arts from Hunter College. In the Spring of 1963, Derby was teaching elementary school in Yonkers, New York, when she was recruited to join the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC pioneered many grassroots, decentralized strategies to fight white supremacy in America and advance Black communal progress, and Derby was excited by the prospect of joining the civil rights movement in Mississippi to work with organizers in Black communities.

The legendary activist Bob Moses, who shaped SNCC’s philosophy under the mentorship of Ella Baker, asked Derby to attack Mississippi’s onerous literacy tests that restricted the right to vote in the state. The idea was for Derby to establish an adult literacy program at Tougaloo College, a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) in Jackson, and, by teaching basic reading and writing skills that could be objectively measured, Black voter registration could be facilitated. Her title was SNCC Field Secretary in voter registration.

After attending the March on Washington as one of the organizers in August 1963, Derby moved to Mississippi to work out of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) office near the Jackson State campus, another HBCU. Unique to Mississippi, COFO was Bob Moses’ brainchild, meant to coordinate under one umbrella the work of diverse and often competing civil rights organizations, including SNCC, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

Her photographs capture the people and work of the movement

as part of a larger folklife of activism.

Initially, Derby agreed to work in Mississippi for one year but spent nine more years in the state, advocating a diverse array of tactics for Black advancement and documenting nearly every stage of her work with her ever-present camera, a practice of photography that she kept up for the rest of her life. Her hundreds of thousands of photographs document the everyday nature of the movement that was grounded in community and traditions of organizing and activism passed down generationally. Her photographs capture the people and work of the movement as part of a larger folklife of activism.

During the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project, better known as Freedom Summer, Derby founded the Free Southern Theater with John O’Neal and Gilbert Moses in order to provide African Americans free access to the arts. Freedom Summer brought approximately 800 activist volunteers to Mississippi to engage in voter registration drives and Freedom Schools. The goal was to bring about political, economic, and social equality for Black people through education, and the Free Southern Theater contributed to the educational project while providing an aesthetic dimension.

According to Derby, the founders believed the Free Southern Theater could be “a crucial tool in improving the overall lives of African Americans, to strengthen Black consciousness, communication, self-knowledge, self-dignity and creativity through the presentation of new information through plays with educational content, cultural expansion and situational relevance to the universality of issues of human dignity.” 2 By 1980, the Free Southern Theater had evolved into Junebug Productions, which continues to advance its founding principles.

During the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project, better known as Freedom Summer, Derby founded the Free Southern Theater with John O’Neal and Gilbert Moses in order to provide African Americans free access to the arts.

In the spring of 1965, Derby returned to her roots as a teacher and joined Head Start, an early childhood education program that emerged from the work of civil rights activists. She served as the head teacher in Durant and Holly Springs, Mississippi. Once again, the idea was to use education at the earliest ages in the Black community to lay a foundation for advancement.

Later that year, Derby pivoted again and became an organizer and member of the Poor People’s Corporation and the Liberty House Handcraft Cooperatives. Through the production of home goods from quilts and other crafts to foodstuffs, Black women in particular throughout Mississippi were able to create a coordinated economy built around knowledge that was rooted in folkways.

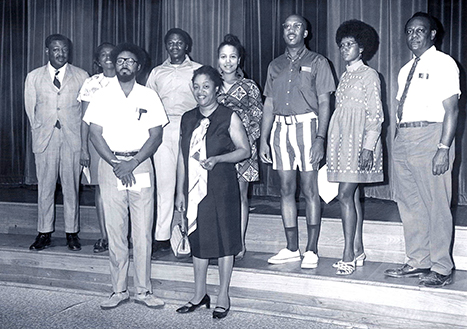

As part of her diverse work with SNCC, Derby joined Southern Media, Inc., a documentary still photography and filmmaking unit based in Jackson, and was later hired as a part-time art instructor, exhibit coordinator, and art exhibitor at then Jackson State College (today Jackson State University).

While Derby never attended a HBCU, she appreciated the time she spent at both Tougaloo and Jackson State and learned much from the work being done there as “safe havens for the development of Black consciousness, pride and the presentation of Black arts, culture and academic scholarship.” 3

At Jackson State in the fall of 1970, Lawrence Jones, the head of the art department, hired Derby to teach his courses on African American, Caribbean and African diasporic art, while he was on leave attending graduate school at the University of Mississippi. That appointment gave Derby the chance to get to know the novelist and poet Margaret Walker, who was on the English faculty at Jackson State.

Eventually, Derby joined Walker’s staff at the Institute for the Study of the History, Life, and Culture of Black People (today the Margaret Walker Center), which Walker had founded at Jackson State in 1968. One of the first Black Studies programs in the nation, Walker’s Institute stood at the forefront of the field and hosted some of the first national and international conferences on the topic.

Margaret Walker recognized Derby’s interest in Black art and culture and respected her photography. When Walker learned that Derby had a large African sculpture, fabric and musical instrument collection from her visits to Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana, and the Ivory Coast, she asked Derby to exhibit some of her African artwork for the Institute in December 1970.

While Derby served on Walker’s staff, she was there with her camera to document many of the artists and scholars who came for programs on campus. Derby captured visits from poets like Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, and Gwendolyn Brooks, and she photographed the groundbreaking 1973 Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival, featuring thirty of the leading Black female writers in the country. More than anything, Derby was moved by being part of an Institute “that celebrated and embraced black pride and consciousness.” 3

Derby’s time on the Black Studies Institute staff deepened her appreciation for the power of folklife as a cultural and intellectual force. She witnessed the Black Arts Movement and Black Studies rise from the rich cultural heritage of African Americans and from the demands of the civil rights and Black Power movements.

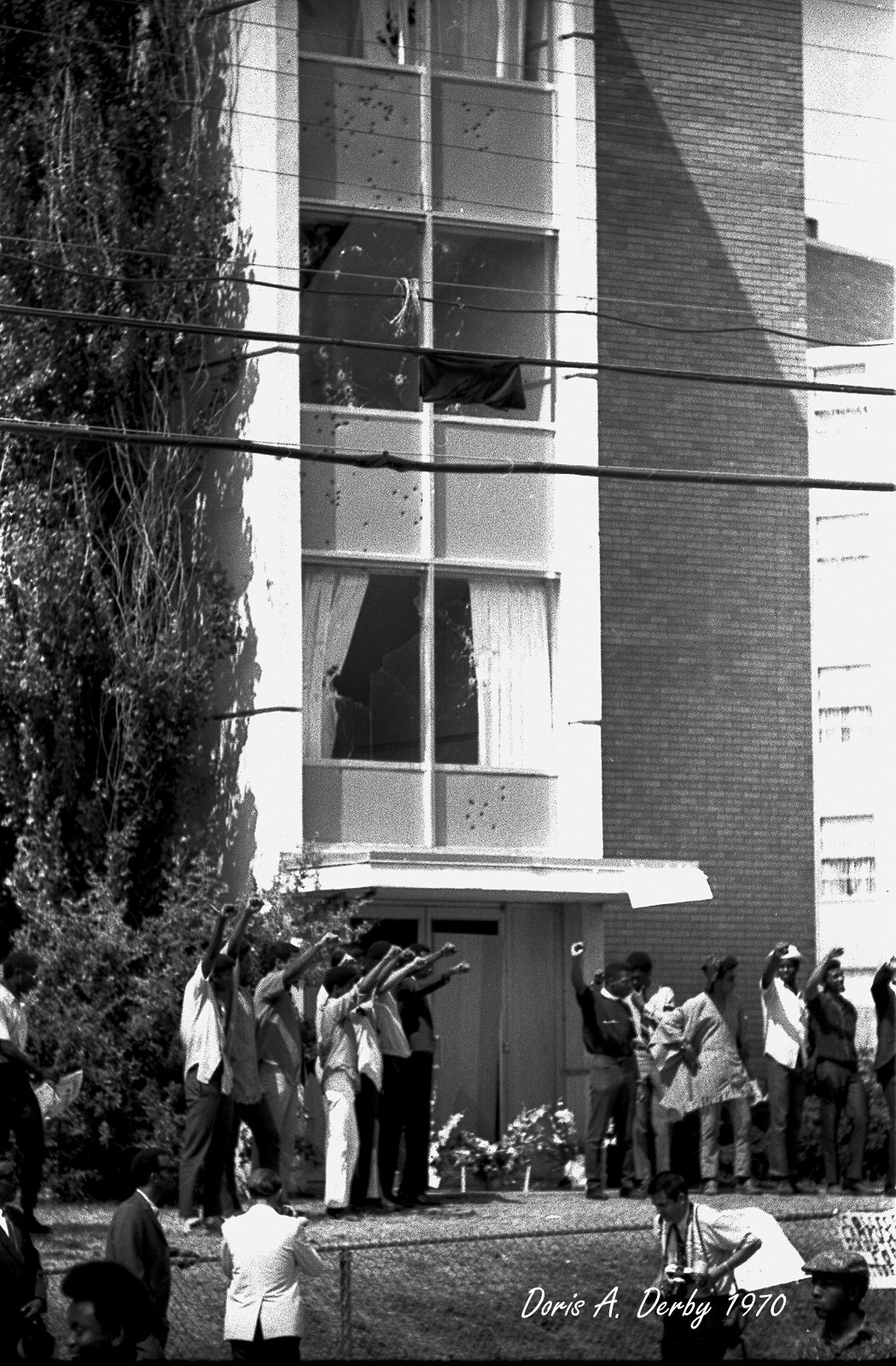

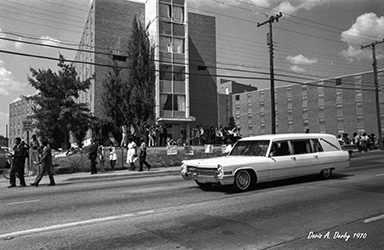

In May 1970, Derby was at Jackson State when city police and Mississippi highway patrolmen marched on campus and fired nearly 500 rounds of ammunition into a women’s dormitory. Twelve people were shot and dozens injured in the chaos. Two young men, Phillip Lafayette Gibbs and James Earl Green, were murdered. No police officer was ever held accountable.

In the aftermath of the shootings, Derby photographed the protests, the funeral of James Earl Green, and the procession to the cemetery. Her images of the Gibbs-Green tragedy tell the story of the continuity of state-sanctioned violence aimed at Black communities throughout American history.

In 1972, Derby left Mississippi. From 1975 to 1980, she pursued a Doctor of Philosophy in anthropology from the University of Illinois. With the academic training of a scholar grounded in documenting folklife, Derby was prepared to launch the next stage of her career.

From 1990 until her retirement in 2012, Dr. Derby was Georgia State University’s founding Director of African American Student Services and Programs and an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Anthropology Department. At Georgia State, Derby was responsible for organizing programming similar to what she witnessed at Jackson State through Margaret Walker’s Black Studies Institute.

In 2011, Derby was honored with the Georgia Humanities Award by the Governor of Georgia for her work at Georgia State and for her photography depicting the life of struggling African Americans who defied the post-emancipation status quo brought about by political, economic, social, and cultural domination and exploitation. Her images have been exhibited globally in museums, galleries, universities, and websites including the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

Through her life and career immersed in African American cultural production, Derby has not only documented the power of Black folklife,

she has contributed to it.

Derby’s work and legacy have been recognized in several publications, documentaries, and websites. She is a contributor to Hands on the Freedom Plow, a book that contains fifty SNCC women’s contributions to the civil rights movement. She has two books. The first is entitled POETAGRAPHY: Artistic Reflections of a Mississippi Lifeline in Words and Images: 1963-1972. It contains a combination of the poetry and documentary photographs she created while working in Mississippi. Her second book, PATCHWORK: (PPP) Paintings, Poetry and Prose; Art and Activism in the Civil Rights Movement, 1960 – 1972, appeared in 2021.

Through her life and career immersed in African American cultural production, Derby has not only documented the power of Black folklife, she has contributed to it. Her story, as revealed in this oral history, is a testimony to her lifelong commitment to this work and to the uplift of her people through it.