Art-making was M.B. Mayfield’s refuge, his precious thing.

There was from Ecru a Black man making art by himself in a broom closet at the University of Mississippi because there was not a single classroom on campus where he was welcome to be a student. 1 The Black man was M.B. Mayfield. The time was 1949. The story is a long one, because a story about a Black son of Black sharecroppers spending two years listening in on art classes at a segregated, all-white university in Mississippi must be long. This version is shorter though, and it begins not with a person, place, or thing, but with an idea: otherwise.

Above: “Baptising”

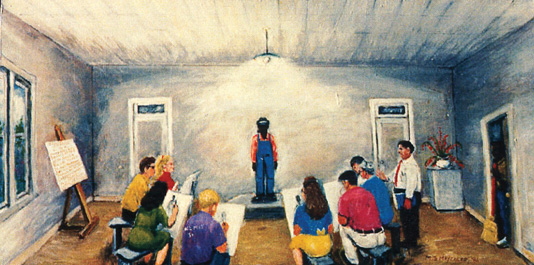

Right: "Dr. Purser's Drawing Class"

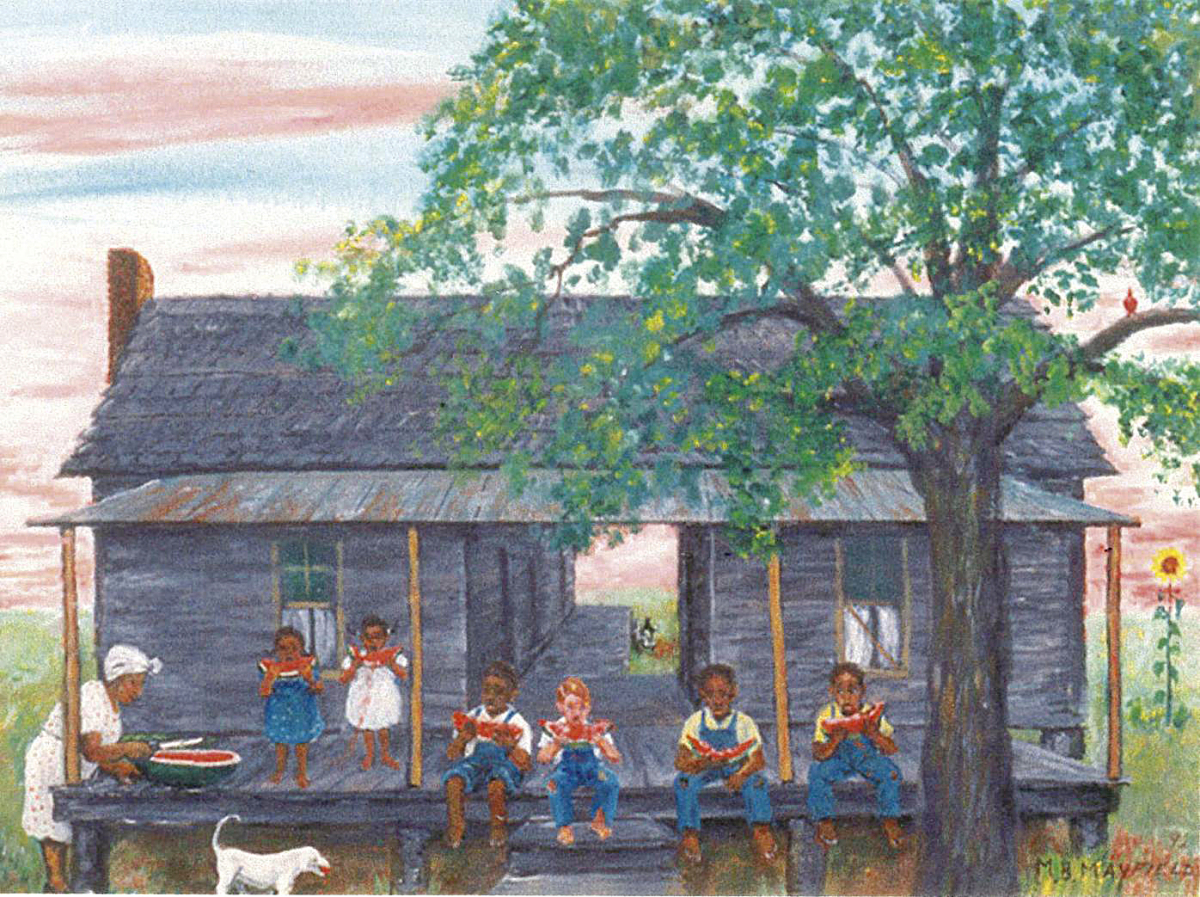

Photos courtesy of David Magee from his book The Education of Mr. Mayfield: An Unusual Story of Social Change at Ole Miss

In common parlance, “otherwise“ means something like "in circumstances different from those present.” It is often used to introduce a contingent possibility, a possibility that depends on something else. If Thing A doesn’t happen, then Possibility B will become so.

Or: A, otherwise B.

In Blackpentecostal Breath, Religious and African American Studies scholar Ashon Crawley positions “otherwise” as something more. It references “alternative modes, alternative strategies, and alternative ways of life (that) already exist.” In this formulation, the presence of an alternative possibility does not depend on anything else. It is on its own. It comes first, even as it is threatened and denied by systems of power and domination (e.g., racism, sexism, homophobia). Here, Possibility B already is, and it is both regardless and in spite of Thing A’s denial of it.

Or: otherwise B; in the face A.

Crawley’s otherwise does not ask or suppose. It allows. Like M.B. Mayfield.

Yet, to be Black in any Mississippi village back then (now, and ever) was to be otherwise too. It is to be

otherwise first.

M.B. was born in Ecru, Mississippi in 1923. At the time, Ecru was more village than town, with less than 1,000 residents; and at that time, to be Black in any Mississippi village was to be confined. Confined to the system of debt peonage that gripped the South after the fall of American slavery (e.g., sharecropping and tenant farming). Confined to farm living and the back-breaking, time-consuming work that it required. Confined to separate and under-resourced social institutions, dehumanizing stereotypes, and violence. And, if the State and everyday white folks had their say, confined to no dreams and limited futures. That is the place where M.B. Mayfield was born and raised, a place of confined dreams. A place where, for Black folks, all possibilities were supposed to depend on something else.

Yet, to be Black in any Mississippi village back then (now, and ever) was to be otherwise too. It is to be otherwise first. Otherwise family and community; in the face of labor exploitation and plunder. Otherwise blues and baptism; in the face of cotton and Mississippi Augusts. Otherwise Black; in the face of everything that sees Black as worthy only of the least, if that much. Otherwise M.B. Mayfield; in the face of a world that would not have him.

Photo courtesy of David Magee from his book The Education of Mr. Mayfield: An Unusual Story of Social Change at Ole Miss

Before M.B. Mayfield was 10, he lost five of his eleven siblings and his father to tuberculosis, the untreatable illness that devastated poor farming communities in the U.S. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. When his mother Ella remarried, she chose another local farmer, a man that Mayfield called Papa Charlie. A man that M.B. grew to resent. Papa Charlie sensed that there was something different about M.B., something that needed to be sweated and worked away. So he worked, sweated, and worked M.B.

M.B. felt alone. Some of his surviving siblings had left to work on other farms in the area. Some were kept from work by recurring sickness. And some were just more agreeable to Papa Charlie. M.B. worked and worked, until he almost died like his father and siblings had. His art kept him.

Art-making was M.B. Mayfield’s refuge, his precious thing. Nothing could keep him from it. Until the demands of farm work pulled him from formal schooling at 13 years old (eighth grade), Mayfield would use school supplies to draw—simple pencil sketches of scenes from his memory or interpretations of comics from the copies of the Memphis Commercial Appeal that lined the walls of the Mayfield house. Occasionally, his mother would buy pencils and paint for him.

As he sketched, mixed, patched, and pieced, he repeated to himself

a simple refrain: "I may become an artist yet."

When M.B. didn’t have all of the art supplies that he needed, he makeshifted his own. Dr. Kimber Thomas defines makeshifting as “making do,” or “patching and piecing” together objects made for one domain in order to use them in another. Mayfield was an expert patcher and piecer, especially of things natural. Mayfield was a farmer after all. He mashed flowers and berries to make paint. Red zinnias. Morning glory blossoms. Blueberries and Black. He painted on masonite, ironing boards, and whatever else he could get his hands on. He made papier-mâchete to make sculptures. As he sketched, mixed, patched, and pieced, he repeated to himself a simple refrain: "I may become an artist yet."

I may become an artist yet. It is an otherwise claim. It begins as the same sort of speculative wondering that “otherwise” connotes in everyday usage. “I may become,” is tentative. Contingent. The becoming seemingly depends on something else.

Artist, unless.

According to these politics, Black people were not artists. They were barely people.

Mayfield's “yet” is a re-orientation though. It was M.B. allowing something for his life that unsettled the normative expectations of the world around him. Especially expectations around race, gender, and masculinity. The same politics of confinement that attempted to define Black life in 1940's Mississippi had no room for M.B. Mayfield. According to these politics, Black people were not artists. They were barely people. Black boys and men were not supposed to paint. They were supposed to plow. Not make, dig. Yet, M.B. Mayfield did.

Otherwise, artist.

In a recent essay, Crawley writes of otherwise: "to begin with the otherwise as word, as concept, is to presume that whatever we have is not all that is possible…Otherwise is the enunciation and concept of irreducible possibility, irreducible capacity, to create change, to be something else, to explore, to imagine, to live fully, freely, vibrantly."

Otherwise, Mississippi.

For much of his life, M.B. Mayfield was known by what would appear to be his initials: M.B. His fraternal twin brother too: L.D. But the letters were not initials in a technical sense. They did not stand for anything beyond what they were. Names. When L.D. was drafted to serve in World War II, he imagined himself otherwise: Lucas Daniel. M.B. imagined otherwise too.

Maurice Brown Mayfield saw otherwise, and lived otherwise, and made otherwise, which for him was a world where people know, where people create, where they realize themselves and where they enjoy life.

“I did adopt a name for my initials,” M.B. said in a conversation about his journey in art-making. “Do you want to hear them?” He asked the unseen interviewer.

“Yes.”

“This, this here is,” M.B. stuttered, an allowance. “This is Maurice Brown Mayfield.”

Maurice Brown was otherwise.

In 1949, M.B. Mayfield accepted a job on the custodial staff at the University of Mississippi and moved into a living space in an on-campus art gallery. The opportunity had come after Stuart Purser, chair of the university’s art department, saw some of Mayfield’s art—displayed prominently on the front porch of the Mayfield house—during a summer drive through Ecru. Mayfield’s art inspired Purser. Before he left, Purser invited M.B. to the university. Though not as a student. It would be another 13 years before the University of Mississippi would admit its first Black student. Purser explained that Mayfield could come work at the university as a custodian and, while he was there, listen in on art classes from a broom closet near the room where Purser taught

M.B. Mayfield worked and unofficially audited classes for a year and a half. Then, in 1950, he returned to Ecru to care for his sick mother. When she died, he moved North to Wisconsin to be near a sister. Maurice was North when James Meredith became the first Black student to officially enroll at the university. Although the two men never met, a university architect speculates that they both spent time in the same classroom—on the third floor in Peabody Hall.

In 1967, Mayfield left Racine to return South, home. He would again work as a custodian in an art space, this time at the Brooks Art Gallery in Memphis, which he had visited in 1950.

Photo courtesy of David Magee from his book The Education of Mr. Mayfield: An Unusual Story of Social Change at Ole Miss

M.B. Mayfield died in 2005. Over the course of his life, he produced hundreds of sketches, paintings, and sculptures, most of them depicting the vibrant mundanities of life in rural Mississippi: Dinner on the Ground at Second Baptist. Pickin’ Cotton. Fishing. Sugar Puddin’. Boys Eating Melon. Skinny Dipping. Headed for the Gin. Ecru Blues. Fun in the Dust. The scenes are striking in their simplicity. And colors. And in their emphasis on landscapes and the natural. And in how they reveal Mayfield's evolution as an art-maker. And in how they insist on humanity—for Black Mississippians especially—in the face of a reality bent on denying it.

And in their beauty.

That is one of the wonders of otherwise—as word, as concept—and one of the things that ties M.B. Mayfield to the broader story of Black freedom and organizing in Mississippi: beauty. What does it take to believe in a possibility unbounded, a possibility that does not depend? Sight. Or, a vision of what the world could be if it were really a beautiful world, as Harvard Ph.D. W.E.B. Du Bois said in tribute to his friend and contemporary Carter G. Woodson in a 1926 speech. M.B. Mayfield had sight. He saw beauty; in the face of a world that took so much from him (and people like him), and asked so much of him (and people like him), while denying so much of him (and people like him). In his art and in his life, he seemed to be seeing what Du Bois was saying: we have the true spirit, we have the Seeing Eye, the Cunning Hand, the Feeling Heart. Not perfect happiness, but plenty of good hard work, the inevitable suffering that always comes with life; sacrifice and waiting, all that. Maurice Brown Mayfield saw otherwise, and lived otherwise, and made otherwise, which for him was a world where people know, where people create, where they realize themselves and where they enjoy life. 2

Footnotes

- ^ In 1926, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People awarded the Spingarn Medal—awarded for "outstanding achievement"—to Carter G. Woodson, author, historian, Harvard Ph.D., and the "father of Black History Month." At the award ceremony, Woodson's friend and contemporary W.E.B. Du Bois delivered remarks that have since been published under the title, "Criteria of Negro Art." The cadence and structure of this opening line signifies on those remarks, in particular the line, "There is in New York tonight a black woman molding clay by herself in a little bare room, because there is not a single school of sculpture in New York where she is welcome."

- ^ The italicized words are taken, verbatim, from "Criteria for Negro Art," remarks made by W.E.B. Du Bois in 1926.