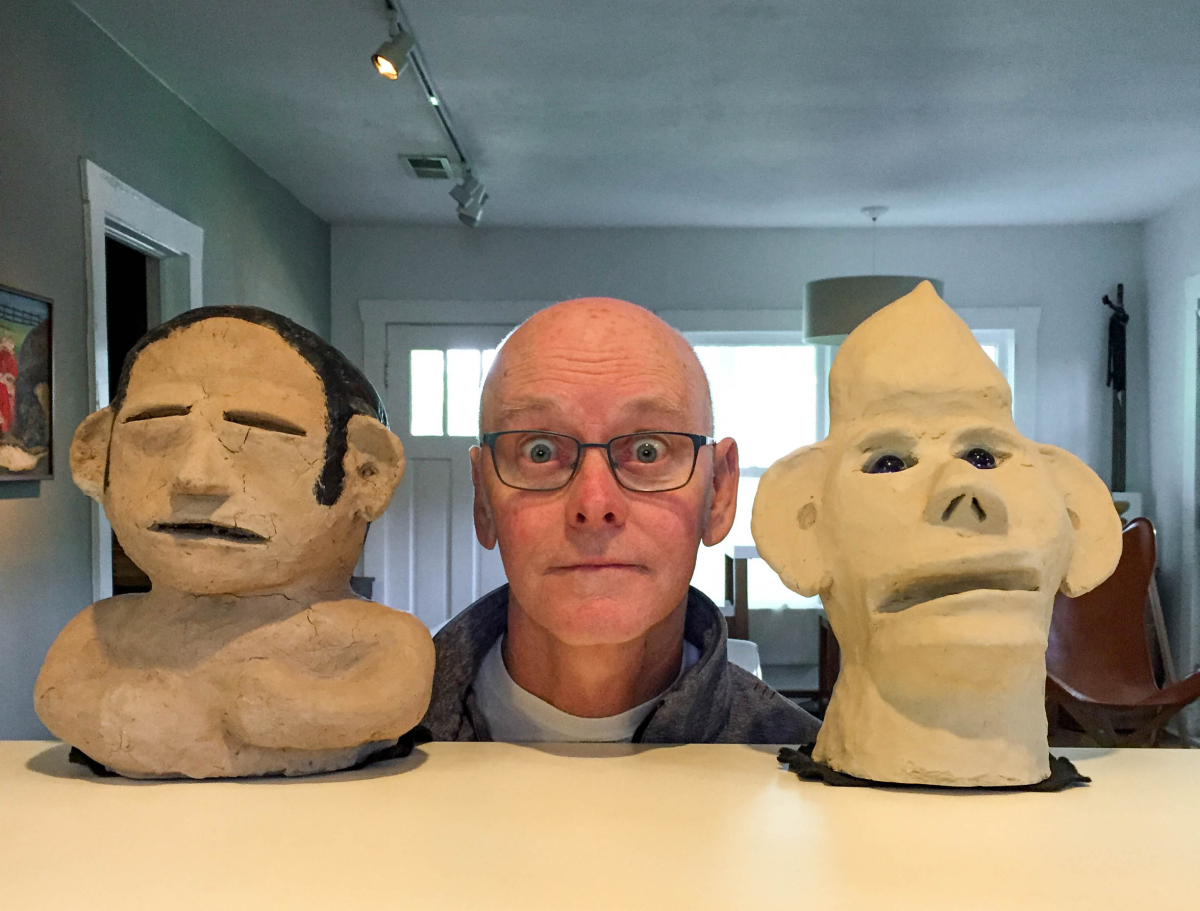

As you step inside the home of art collector Terry Nowell in Austin, TX, you are immediately surrounded by numerous works from America’s great self-taught artists. Were it not for the bedroom and kitchen tucked into the back, you might feel as though you’d entered a small museum or gallery. Nowell has committed himself to understanding the work of artists who developed their talents while entirely removed from any mainstream art movements. In particular, he has emerged as a major collector of the Mississippi sculptor Burgess Dulaney, whom he began visiting in the early 1990s. Terry keeps nearly 150 of Dulaney’s playful—and often haunting—mud sculptures on display in his home. I spoke to Terry about collecting, his relationship with Dulaney (who passed away in 2001), and Dulaney’s work.

Before we sat down for our interview, Nowell read aloud a passage from the introduction to Chuck and Jan Rosenak’s 1996 “Contemporary American Folk Art; A Collector’s Guide”:

“[W]e found a growing response within ourselves to the richly diverse folk art of our native land, art engendered within a broad range of social and economic circumstances, and art that underscored the meaning of the American experience. We began to realize that, after all, academic theoreticians can advance the arts only so far; after a time great thoughts bore us, and we say to ourselves, ‘Ho for the adventure of discovery. Ho for dirt-track America. It will restore us.’”

Rian Haight: I know you’re originally from Mississippi. What county are you from?

Terry Nowell: I was born in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in Neshoba County. That's the county where the three civil rights workers, Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney were killed in the sixties. There's a movie, Mississippi Burning, that was made about Neshoba County. I was between six and ten when all of the civil rights activity was going on in Mississippi. It was a very scary time and I didn't know what was going on. I had no idea the scale of what I was living through. I remember the Seabees coming and walking arm in arm across our property to try to find the three civil rights workers. I think I always tried to escape Mississippi. I ran away as fast as I could when I turned 18.

RH: And then where did you go to school?

TN: I went to University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg. And that was a good escape. That was a little ways away from where I grew up. And then that eventually led me to coming here, to Austin, through a friend that I knew from Mississippi who moved here to go to the University of Texas at Austin. She said come visit, and I came, and I fell in love with it immediately. That was in 1979, and I moved here in 1980.

RH: How did you become interested in collecting art?

TN: Well, I'm not sure exactly. I've always been a collector of something. Growing up, as a teenager, my friends and I would try to find what we thought were valuables in old abandoned houses. We’d ride our bikes off to some slave shack and find broken bottles. We’d find mason jars or glass top jars. That’s what we were doing back in the sixties. We were trying to find these jars and then insulators. We'd spend a lot of time on the railroads camping, playing up and down the railroads, and we would try to find antique insulators. I had this want, or this desire, to be collecting something. And then I went to college, and I didn't have any money in college, so I collected a few little things here and there. And then I came here to Austin, and I did collect some antiques. I got into Craftsman furniture and started buying Stickley furniture back when it was cheap. So I was collecting furniture and stuff like that and a few antiques. And then as a chef I catered this dinner for a friend who’s dad collected art. I didn’t know what kind of art he collected. My friend and her husband had made this honeymoon trip through the South collecting art and they’d gone to see Burgess. And I went to their house and saw the first of five pieces that they had gotten directly from him on their honeymoon trip. At first I thought the pieces were pre-Columbian. [At this point Nowell picks up a very pre-Columbian looking Dulaney piece and says, “You don’t learn that in school!”] And so she said, “You should go visit him in Mississippi the next time you're there.”

RH: And that’s how you came to meet Burgess?

TN: Yes. They drew a map for me to take on the back of a cocktail napkin. All of which, well, the details were wrong, only the vagaries were there, and so we didn’t find him on the first ventures down these roads. About three months later I took my mother and grandmother there and we went to try to find him and finally we hit the right road. We went down this road and there he was. He had about six or eight, as he called them, mud heads made and they were all still wet. We sat there with him and he shared stories with my grandmother about his life and from that moment on it was history. I continued to visit him two or three times a year up until his death in 2001.

It came from somewhere deep inside him. There was this eagerness to create, and it was certainly outside the establishment.

RH: What was Burgess’s early life like, before he was discovered as an artist?

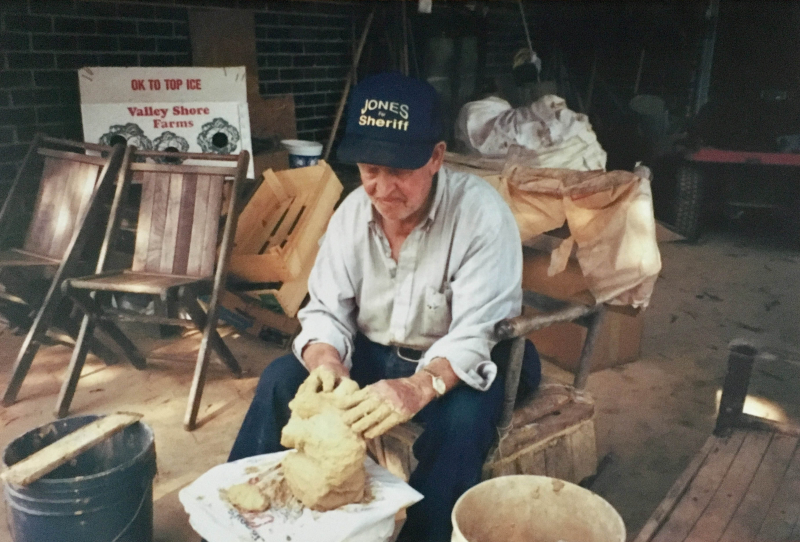

TN: I think that’s a tough one. I got snippets of his life from family, but I believe everyone was dead by the time I met Burgess except one or two sisters who lived down the road. They told me that he had always played with mud. Burgess told me that his brothers and sisters made fun of him for playing with mud. Burgess couldn’t read or write. He had never left the county he was born in until he had a heart attack and was taken for surgery. He didn’t go to school other than a very short period of time. One time he told me third grade and one time he said second grade. He grew up on this farm in a fairly isolated environment and had always kind of played with mud. That's what he did. He never really made this art to sell it to make a living off of. He never considered himself an artist. He never said, “I'm an artist.” And he never set out to be an artist from what I could see. I mean this came from somewhere totally different. It came from somewhere deep inside him. There was this eagerness to create, and it was certainly outside the establishment.

As far as I know, he grew up with these siblings on this farm and just did farming. And they’d occasionally sell a pig, or maybe a cow, I'm not sure, but I know they had a pig farm and they sold cotton. They weren't plantation owners by any means, but everybody would have a small cotton field in those days. And they had enough for the family to pick and sell to make money to survive on. They lived off the land. They fished. They hunted. They had woods behind the house. And they grew what they needed. Burgess was married to this woman named Effie. And he was married to her until she died in the mid 90s. Burgess lived in the house there on that property that his dad had built in the mid-to-late 1800s.

We sat there with him and he shared stories with my grandmother about his life and from that moment on it was history. I continued to visit him two or three times a year up until his death in 2001.

RH: How many pieces did Burgess produce over the years?

TN: I’ve tried to document all I can, and every time I hear about a piece I keep a record of it. And so most people agree that he probably made four to five hundred pieces of art.

RH: And the clay that he was using was all from the family property?

TN: At the beginning yes, until he got older and couldn't get down there to get the clay. He dug from three pits on his property. One right by the driveway, probably the earliest pit from what I can find. That’s how I date a lot of the pieces is from these three different pits. The mud is distinctly different from each one. And then the timeline of the pit, especially the big one down there by the creek, the mud changes as he went into the clay. Pure kaolin has a certain property to it, whereas at first it had a lot of iron in it. So you see a lot of pieces oxidize over the years and turn dark, which I love. I think it adds this beautiful, mysterious kind of magic to the clay that I’ve never seen anywhere. It’s almost like a natural raku finish on the clay. So he dug these three pits and one more up on his brother-in-law’s property.

So you see a lot of pieces oxidize over the years and turn dark, which I love. I think it adds this beautiful, mysterious kind of magic to the clay that I’ve never seen anywhere.

RH: About how much would Burgess sell his pieces for?

TN: Fifty dollars. They were across the board fifty dollars.

RH: Regardless of the size?

TN: Yeah.

RH: You knew Burgess fairly well. What was he like as a person?

TN: He was the most jovial, sweetest guy and he had this great little voice. And the first thing he’d say was “hoo-wee.” “Hoo-wee you didn’t come from way over yonder down here to see me?” He was amazed you'd come from Texas. He was always jovial, he was very nice and he told really fantastical stories. He had a very vivid imagination as his work shows. But it came through in conversation. He would tell me these wild stories. The greatest part of this to me was being able to spend time with these people. Burgess and I would occasionally sit there and not say anything. We would sit there sometimes for ten, fifteen minutes and never say a word.

RH: Was there a tradition of making mud sculpture in Mississippi?

TN: Three people that I know of, but that’s all. And there must be more. We have Son Ford Thomas, a blues musician in the delta of Mississippi who’s incredibly well known. He’s from Leland, Mississippi. And Juanita Rogers from Alabama. And then Burgess.

RH: Were these artists aware of each other?

TN: Oh, absolutely not. Absolutely not. There’s no way. Okay, and then go right across the border from Burgess in a foreign land, Alabama, 28 miles away, and there you've got Jimmy Lee Sudduth. Sudduth was a blues musician--not a recorded Blues musician like Son Thomas who made recordings in the 50s and 60s. And you got a man here painting with mud, right across the border. They never met each other at all. And so Burgess didn’t share, he didn’t set out –that’s the one thing that I loved about this. In seeing people that went out to school and said “I'm going to be an artist,” it had this fakery about it that I never cared for. Compare to this man, these people, sitting in an isolated environment--fairly isolated, some more than others--creating this amazing powerful artwork, never calling themselves an artist. If you said artist or gallery or museum to Burgess he just giggled. I mean, that wasn't his approach. He didn't do this to say, “I'm going to be an artist.” That was one of the great genuine parts of discovering this art, finding people that had this unbelievable connection, somehow, with another world. And they didn't do it to make money. He did not do it to make money.

RH: Where do you think the inspiration was coming for Burgess’s sculptures?

TN: He and the brother-in-law dug in these pits in Native American mounds there on his in-law’s property. The Mississippian Indians 1 of course had built mounds. And they had looted in a mound there which, you know, today you’d go to prison over it but in the 50s and 60s it was no big deal. They just dug for fun. They’d try to find arrowheads and stuff. And they found Native American pottery. And so I can guarantee that was an influence. I think you can see it in a lot of the work, that there’s this tribal feel to it. He and his brother-in-law also went to flea markets and they would see odd stuff like face jugs. In that area at the turn of the century there were eighty-five to ninety family potteries who made mostly utilitarian vessels but one thing that was also common in that area was face jugs, you know, effigy jugs. It was an African American tradition, and they were called spirit jugs also. I think he saw those at the flea market, and they were an inspiration as well.

And they found Native American pottery. And so I can guarantee that was an influence. I think you can see it in a lot of the work, that there’s this tribal feel to it.

RH: How was Burgess first discovered as an artist?

TN: Some of the earliest that I could find out of people learning of Burgess was from a guy named Robert Reedy. Robert Reedy told me that he was at a party in Itawamba County, and a woman overheard him say that he taught art at the local junior college. Her ears perked up, and she told him, “You know there’s this old fella that comes to the funeral home, and he comes once a month to pay his burial insurance.” Well that’s very common in the South. My grandmother paid her burial insurance once a month, five dollars a month her entire life, which paid by the time she died $10,800. And it only paid out $110 on her casket or something, you know, the insurance rip-off industry. And so she collected burial insurance, and Burgess would come there once a month to pay his burial insurance. And she said, “What he does, he brings me these weird mud things.” And Reedy was like, “What do you mean weird mud things?” She started describing and he just said, “I have to see them.” And she said, “I don't have them, I've destroyed them all. I’ve taken them to the back of the funeral home and washed them down with a water hose because I don't want them.” She thought they were kind of scary. But it turned out that she still had the most recent one and the next day Reedy went to see it. And he said immediately I've got to meet this man, and so she took him out to Burgess’s house, down this kudzu lined dirt road. So at that time he had given pieces to the funeral home, he had given pieces to, as they call it, the prescription center, which means the drugstore. And to the local veterinarian. The veterinarian had about ten or twelve pieces. The prescription center had about six or eight amazing pieces. And then she was throwing them all away. Who knows how many he'd given her. So he was sharing the pieces with other people, but as gifts. He bartered work on his animals with the veterinarian for them because the veterinarian loved them. I haven't seen him in twenty years but when I was there he adored the pieces. And so did the prescription center people. The drugstore people wouldn’t let you close to them. They had them on display at the drugstore there in Itawamba County, and they absolutely loved them. And so Robert Reedy, I believe, in turn called Dr. Warren Lowe who's a psychologist in Lafayette, Louisiana, who collected self-taught art. And they came, and I think they maybe told the Rosenaks. Or at least that's the lineage that I got. And the Lowes did the first show in Louisiana, Baking in the Sun in 1987.

RH: Burgess was aware his work was appearing in museums and being collected seriously while he was alive?

TN: Yes. And during the Atlanta Olympics in 1996 a group came to Burgess and asked him to do three pieces for the Olympics. And he told me that they took him to the school to get him to do the pieces and they provided clay. They took the pieces back to Atlanta, and they had them mocked up in giant size--about twelve feet tall and twelve feet wide--in Olympic park. And supposedly they’re still there in Olympic park. And that was one of two times that Burgess left the county. A great nephew came and picked him up and took him to Atlanta to see his pieces about a year before he died. And Burgess told me after he’d been, he said the word, “Zoo-another.” He said, “They had ‘em over there in some old ‘zoo-another.’ Made ‘em big. Big enough to walk all the way around ‘em.” So, he was fascinated that they were there and proud, but he really didn’t know. But that was a way that he got out there and had some influence.

RH: Earlier you told me the story of how you were visited by some Tibetan monks, and they were deeply moved by Burgess’s sculptures. Maybe we can close with that story?

TN: I had seven Buddhist monks from Tibet come here for a dinner once, and they were blown away. And they couldn't stop. I had a couple pieces out, and they just kept their hands on them. I loved it because I was like, they really feel what I feel with this work. They told me that they feel some unbelievable energy in these pieces, and they think that when a piece is fired it’s lost. The fire kills that energy. And they've never felt it before in effigies like this. They were just practically in tears over it. And it was one of the best experiences because I have had people in my house who don't see anything. And that's fine. They don't even see the art at all. And other people walk in and they go, “What is this stuff? Where’d you get this? Did you get this at Hobby Lobby?” [Laughs] They don’t have a clue. And other people are well versed, so you get all kinds of reactions. But this reaction from the monks, they were really moved.

Note: This interview has been edited for style, length and clarity.

Footnotes

- ^ Terry uses this term to refer to the American Indian nations classified within Mississippian culture.