I’ve always loved obscure history and stories of real people, and once you start digging around, there are so many amazing stories of people that have been completely forgotten in history.

Lee Harper is an Oxford, MS based artist. She makes dioramas of obscure historical scenes, as well as cultural customs, events and places. In her miniature worlds, skeletons act out history and serve as the main characters of her scenes. Lee has titled this project, History Bones, which is also the name of her website where people can see a gallery of her work on display. The subtitle of this site, “When A Halloween Gag Meets an Artist/History Nerd,” is an apt summation of what viewers will see. Lee recounts that the History Bones project first started as way to entertain her son, niece, and nephews during Halloween and give them a “funny macabre version” of the Elf on the Shelf Christmas tradition. By doing this, Lee started a new Halloween tradition in her family that centered on Bones, who could be found modeled in funny scenes around her house during the week leading up to October 31st. Over the years, Lee’s family tradition has morphed into an ongoing artist series. Lee has made dioramas of the catacombs, St. Roch’s Chapel in New Orleans, Typhoid Mary, Marie Antoinette and the French Revolution, and pioneering stop-motion animator, Ray Harryhausen, working on miniature scenes in his studio, to name just a few of the quirky, spooky, and creative pieces in her oeuvre. In addition to her website, Lee is active on Instagram where she documents her work and tells the backstories to her pieces. During our interview, Lee told me that her dioramas “are just a method of telling a story.” By scrolling through her website and Instagram account, it is clear that Lee is a passionate visual storyteller. Her work is a jumping off point to explore the lesser known moments of history, scary stories, and lives on the fringes.

During our interview, Lee told me that her dioramas “are just a method of telling a story.”

In describing her work on her website, Lee states:

“All of the pieces are about real people, events or customs from some point in this crazy world. The more obscure or bizarre the story, the better. I'm only a FAN of history, so every detail in the images may not be correct, but the written descriptions are as close as I can come. Artistic license has definitely been taken in the images. The goal is to bring some of these subjects out of the dark and deliver them with a bit of my interpretation.”

Lee and I met one afternoon in her studio where she showed me her work, explained her process, and talked about the origins and inspirations of this project. What follows is a selection of moments from our entertaining conversation about History Bones. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

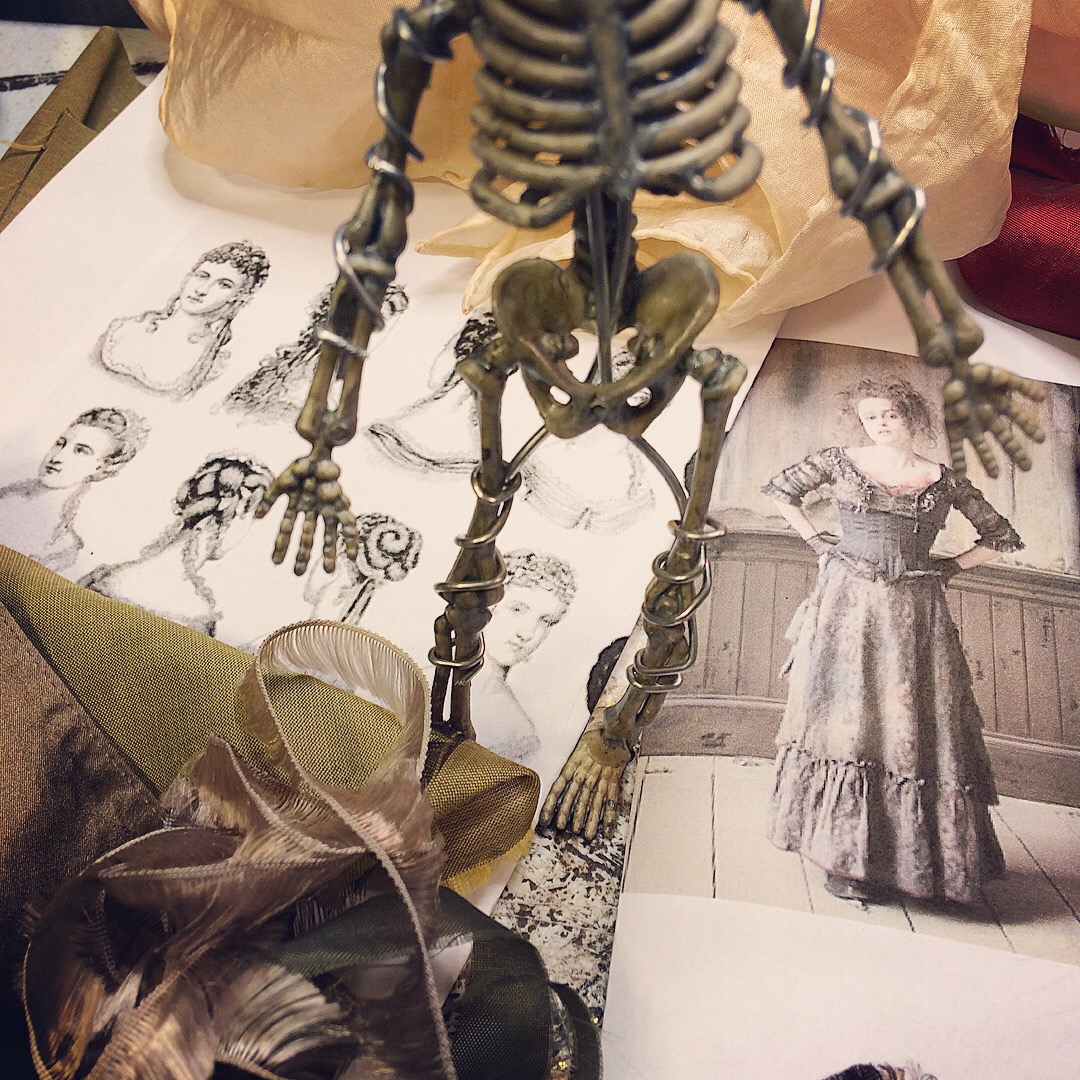

Close up of a figure from Lee’s French Revolution miniature scene. Photo by Lee Harper.

***

Maria Zeringue (MZ): So I guess let’s start with your artistic background. How did you get into art and then how did you come into this work? Do you call them dioramas?

Lee Harper (LH): I do. I either say miniatures, or dioramas. But, dioramas really is a better term for them. I’ve always painted and drawn. I’ve always been making things. I got a degree in art and have made a living from painting and illustration. And like I said, this was my protest against Elf on the Shelf. And I thought, I’m gonna have a really funny Halloween guy that will be a skeleton doing something funny each day of the week up to Halloween. He started out just as a bare skeleton, then he got a hat, then he got a shirt, then he was doing something else. Over three or four years of just the weeks of Halloween, it got more and more elaborate. About four years in [of doing this], I thought, I’m going to do a historical scene, and I got really fascinated. My first one was John Wilkes Booth about to shoot Lincoln at the Ford Theater because I love [the] idea of that couple of seconds of time, the before and the after, where history is forever changed. That split second, you know? I’ve always loved obscure history and stories of real people, and once you start digging around, there are so many amazing stories of people that have been completely forgotten in history. I didn’t even like history in school. I really did not get into it until after I was out of college. And, I know they have to cover a ton of material for class, but the little footnotes and all the little details are what are interesting to me.

The Catacombs diorama. On her instagram page, Lee says that this miniature is inspired by a few of her favorite images of catacombs and ossuaries. Photo by Maria Zeringue.

***

Throughout our conversation, I asked Lee about individual dioramas that I saw on display in her studio, and she happily talked in detail about the historical and artistic elements of each piece that I asked about. In this section of the interview, Lee discusses her Stagecoach Mary piece.

Close up photo of Stagecoach Mary, a legendary mail carrier in Montana during the 19th century. Photo by Lee Harper.

Her work is a jumping off point to explore the lesser known moments of history, scary stories, and lives on the fringes.

LH: This lady has to be a movie at some point. Mary Fields, born a slave in the 1830s, was nicknamed Stagecoach Mary. She ended up in Montana, free somehow and raised animals, grew crops, smoked cigars, swore, [and] delivered the U.S. mail route—like every day, all the time, in rain, sleet, snow. You know what Montana weather is like. That’s why she got the name Stagecoach Mary, because nothing stopped her, including wolves. She has all these crazy stories. She drank men under the table; carried a shotgun and pistols at all times; and according to the Great Falls Examiner, “broke more noses in central Montana than any other person due to her affinity to fist fight men.” Seriously, she delivered mail and parcels to such remote areas that she is credited with helping develop central Montana. Because you can’t develop unless people have some kind of connection to the outside world. Her route kept communication open to the outside world for those who lived in even the most remote corners of the state. She earned her nickname by being so punctual. And, she didn’t retire from that route until she was about 70 years old. She was the only woman in town allowed in the saloons. She was a larger than life just character. And I mean, have you ever heard of this woman?

MZ: No, I’ve never heard of her, ever.

LH: No. Half the fun is when I’m researching stuff. I’ll find two or three other things that I’m like, “Wow! What?” and write that down and come back to that later. You just go down rabbit holes and find all this stuff, and it’s just like, how have you never heard of these people? These people are amazing. I found it in a tiny little Montana history journal, something or other, that somebody had referenced. And I thought, wow, this lady is a force of nature.

MZ: Wow, that’s cool. Well the background on the Stagecoach Mary diorama, did you paint that?

LH: I did. Usually, on these what I do is find images online that fit the time period and have the architecture and the look of what I need. I copy off a bunch of stuff and then collage it together, because it’s never exactly what I need. And then I hand tint it. I copy it in black and white, and then I hand paint it. It just gives it a cooler look. Plus, I mean, every single period [is so] different.

MZ: So is that your process for all of the backgrounds, generally?

LH: Generally. And the first one I did that on was for a very practical reason. It was the French Revolution, and you have an entire city in the background with thousands of people fighting. I thought I'm not painting thousands of soldiers when they're just the background. Once I made one, I realized that it looked great, so I kept doing it that way. I love the look of a hazy, hand-tinted backdrop.

Detailed close up of Marie Antoinette’s ship wig from Lee’s French Revolution diorama. Describing the scene on her website, Lee states, “Antoinette didn't go to her death looking like this but I couldn't resist showing her most iconic look.” Photo by Lee Harper.

MZ: That’s cool, so it’s like a layered collage that you just kind of build with different pieces that you find. And then you print it out in black and white—well, lay it out, print it out, and then hand-tint it?

LH: Yes. So, [the background image] may be from ten different things, but I get the images that I need. I may print out 10 different images and then cut and paste them by hand to get what I need. Then I tint them. And I’m not even pretending that it’s one piece. They’re definitely all collages of some sort.

MZ: Had you ever done anything miniature before you started all this?

LH: Not really. Unless it was just something that I needed that happened to be small. Seriously. The only reason these are miniature, and honestly the only reason that I’m doing these is because of that funny Halloween thing. And that dictated the size of the things. If I hadn’t [started this], I would’ve never thought, “Hey, I want to do something new. I’ll do dioramas with skeletons.” I would have never thought of that, you know what I mean? It just kind of evolved over time into something I never would’ve thought of.

MZ: That’s really interesting.

LH: But it’s so funny [because] my favorite parts are the tiny details. Like the little oil lamps, and the little pipes, little cages. I like to research whatever clothing and details of the time period are needed.

MZ: So what were some of the challenges when you started these? Was there a learning curve in doing these miniatures?

LH: Yeah, one of the major things that I figured out very quickly is like, the little skeletons I use, I buy them in bulk. But they come as just stiff little toys, so you can’t make them stay in any form or fashion. In the Lincoln piece, everybody’s real stiff, because I would bend it and then glue it.

MZ: Oh gotcha, OK.

LH: Then I figured out, if you make a wire frame to then attach to the skeleton, like a body brace of sorts, you can literally bend them to your will. And they’re so much more expressive. Because they’ll stay just like I want them to. I couldn’t have known this at the time, but since most of them are like this now, you can do a little stop motion. I mean they’re not meant to bend a bunch, but they do bend some. These guys, they would’ve never looked this cocky and funny without their wire frames, because that allows for the exact poses I'm going for.

***

Close up of the wire frame that Lee attaches to each of her skeletons to make them more pliable and expressive in her miniatures. Photo by Lee Harper.

MZ: Because it started out with that character Bones, do you think all these dioramas are Bones playing dress up? And he’s existing in this universe? Or is it that it started from this one character and grew into all this other stuff?

LH: I think, in my mind, it started out as one guy. The first few Halloweens it was just the one fellow doing goofy stuff for sure. Once it focused on the historical scenes, I started researching the fascinating culture of skeletons in art, including memento mori, Danse Macabre, and Day of the Dead, just to name a few. For centuries, people have used skeletons in art, and it’s always to remind us that, do what you can while you’re here, because we’ll all end up like this. And it also re-affirms the fact that all these people are gone. I typically don’t do people that are still alive. And it’s not meant to be a gory thing. It’s just meant to be a reminder of memento mori, which translates to “remember you must die.” We need to live for today, just go for it.

MZ: And that’s what you meant when you said it’s meant to be a great equalizer.

LH: It is! Because seriously think about it. If you started with a skeleton, you wouldn’t know whether it was a man or a woman, black or white; where they were from; whether they were rich or poor. You know what I mean? It’s kind of great. Until you dress them or do whatever you do to them, it really is an equalizer.

MZ: So what are the other materials that you use? Does it kind of depend on the piece?

LH: I’ve got cardboard, dirt, rocks, bought moss, moss from the yard, fabric, I have little swatches of fabric. Tons of them. They’re color coded. I find things at Goodwill. I get to use my whole wheelhouse for these. I sculpt clay things. You paint, you carve out of wood. Part of the fun is figuring out how you’re going to make some of this stuff. It’s really fun. I get to whittle a lot, which I love. Oh, and, of course, a lot of things are painted. I needed an angel head for a bust to include in the St. Roch piece and found the saddest broken candle holder at Goodwill with angels on it. I took it home, broke the remaining heads and wings off of it and it turned out perfectly. That sounds terrible, but honestly I think it would've ended up in a landfill otherwise, poor thing. So, if you see me out and about buying strange things, don't assume they'll be used for their obvious purpose.

***

Close up of the St. Roch Chapel in New Orleans. A description of the piece from Lee’s website states, “Offerings, or ex votos, are left there for St. Roch, the patron saint of healing. Plaster body parts, prosthetics, crutches, “thanks” stones and other trinkets are everywhere. The cemetery was created in 1874 after an outbreak of yellow fever that killed thousands in New Orleans.” Photo by Lee Harper.

MZ: Do you keep a list? Are there projects that you want to do but you just haven’t gotten to yet?

LH: All of the above. I have a huge list. And some are different sizes, so they can be done more easily than others. But then, really when I’m starting one, I’ll look through my list and sometimes I’ll find something just like that, and it jumps to the top of the list. It’s whatever I’m most excited about. Because it’s so tedious and time consuming, I have to be really excited about it. You know because I’m basically making them for fun, and if they’re not fun, I’m not making them. Unless somebody has commissioned one, of course.

I pointed out Lee’s Typhoid Mary diorama about the backstory. What follows is her response.

LH: Oh, Typhoid Mary… Hand washing was not a big deal back then, right? And she was a cook for many families. Her specialty dessert was homemade ice cream and peaches, and it was really the only food that she made that wasn’t cooked. She was really known for that dessert. So they think that was the dish that helped spread [typhoid fever], and she’d get taken in and they’d say you know, “We’ll let you go but you have to promise to not be a cook for people.” And of course, when you’re asymptomatic you’re like, “I’m not sick!" Germ theory wasn’t known at the time. She kept going back and being a cook. Finally, she got put on an island for lepers and lived out the rest of her life there because she wouldn’t play nice.

***

MZ: Do you work on multiple pieces simultaneously? Or do you usually just do one at a time.

LH: One at a time

MZ: So how long does it take you to do a piece?

LH: The really crazy ones can take up to a month, and that’s not working all day and all night, but you know what I mean. And then some, like a little one-person figure, like my Jujitsu Suffragette Lady, I could make her in two or three days. I don’t know if you saw her picture, but her outfit and her hat are very much the style of the day. I love that, looking up all the fashion. What are the streets made out of? What would the décor be? Would those miners have oil lamps or electric battery-operated lamps? All that kind of stuff, all those little details.

What’s fun about it is all the little details to get [the diorama] right back to that place in time. That’s actually my favorite part.

MZ: Wow it’s really like world building.

LH: Right, right. I mean you have to. What’s fun about it is all the little details to get [the diorama] right back to that place in time. That’s actually my favorite part.

***

MZ: What other art work do you do? Is this mostly what’s taking up your time when you have free time to do work for yourself?

LH: The past few years, if I have free time, I’d rather be working on these. I've started making commissioned miniatures for people of places that are special to them. Some examples are the (now gone) Hoka in Oxford, a church someone got married in, an old family home, an old business, just anything that has significance to that person.

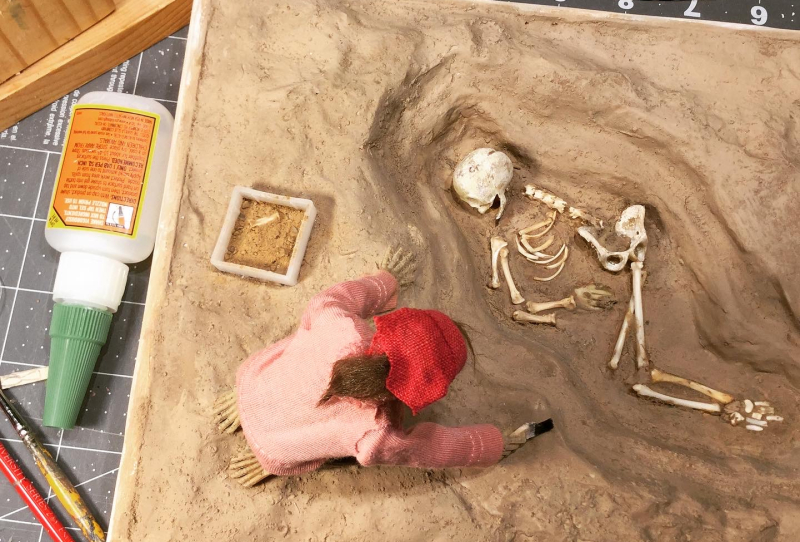

(Left) Close up shot of the Hoka theatre in Oxford diorama. On her instagram page, Lee gives some insight into this piece, “For people not from this area, it was an iconic spot for students, writers, working folks, really everyone here in Oxford during the 80s and 90s.” (Right) A work in progress shot of the Lee’s Mungo Man diorama. Mungo Man, as he is commonly known, is the oldest skeleton found in Australia. The remains were discovered in 1974. Photos by Lee Harper.

MZ: How do you describe your work to people?

LH: I laugh and say, I make stuff. I make a lot of stuff. And frankly, whenever I try to describe these, it sounds hysterical, it sounds ridiculous. I’m like, you know what, let me give you a card, and just go to the website. Because, seriously, I make skeletons and I dress them up and make them do things. It sounds stupid. But, when people see them, they’re like, “Oh my gosh! Okay, that’s not what I thought,” you know. People are always asking, how’d you get started making these? Which is a great question. Because like I said, I would’ve never started with this. Never. It was completely just accidental, and it just morphed and evolved over time.

MZ: I think that’s neat how organic it is.

LH: I know! Yeah. I mean I would’ve never dreamed, I just thought it was hilarious when we first started. You know, he was like one guy having these adventures, but now, it’s totally different.